885

Published on December 24, 2025Custody Without Safety

Deaths in jail and police custody have increased noticeably under the Yunus-led interim government, turning detention into a growing source of fear rather than protection. People are being arrested alive and returned dead, with official explanations offering little clarity and even less accountability. What was meant to be a period of reform has instead exposed a dangerous breakdown in the state’s duty to protect those in its custody.

This is not an abstract human rights argument. It is a clear pattern of deaths, and Awami League activists and leaders appear repeatedly among the victims. Many were detained in politically charged cases, held for extended periods, and denied proper medical care. Their deaths are routinely dismissed as illness or suicide, reinforcing the sense that custody has become a space where responsibility quietly ends.

This is where political responsibility becomes unavoidable. The Yunus government came to power by selling hope, promising restraint, reform, and a clean break from past abuses. That hope has now been exposed as false. Yunus did not merely fail to deliver change; he misled the public, offering reassurance while allowing the same violence to continue under a different name.

His government has chosen silence over accountability and denial over responsibility, creating an environment where abuse thrives without consequence. By refusing to intervene, order investigations, or enforce reform, Yunus has effectively normalized custodial death. What once provoked outrage is now treated as routine. In today’s Bangladesh, arrest no longer signals the protection of law; it signals exposure to a state that has abandoned its duty to keep detainees alive.

The numbers from the past year tell a troubling story. At least 119 people have died in prison custody, while 21 others have died in police custody. During the same period, 26 people were killed in extrajudicial actions, and 106 lost their lives in incidents linked to political violence. Taken together, these figures point to a serious breakdown in how the state is handling detention and public order.

15 Months After the Uprising, 112 Deaths in Custody Raise Alarms in Bangladesh

What is especially concerning is the noticeable rise in deaths inside jails and during remand. This makes it increasingly difficult to accept official claims that each case is an isolated or unavoidable incident. When deaths occur repeatedly across different facilities and jurisdictions, they point to a systemic problem rather than individual misfortune.

Once someone is taken into custody, the state assumes full responsibility for their safety and well-being. That responsibility does not disappear because of illness, prior injury, or alleged suicide. Every death in custody demands transparency and accountability. The continued increase in these deaths, therefore, reflects a clear failure of governance. Under the Yunus government, the state has not only failed to prevent custodial deaths, but it has failed to meet its most basic obligation to protect the lives of those it detains.

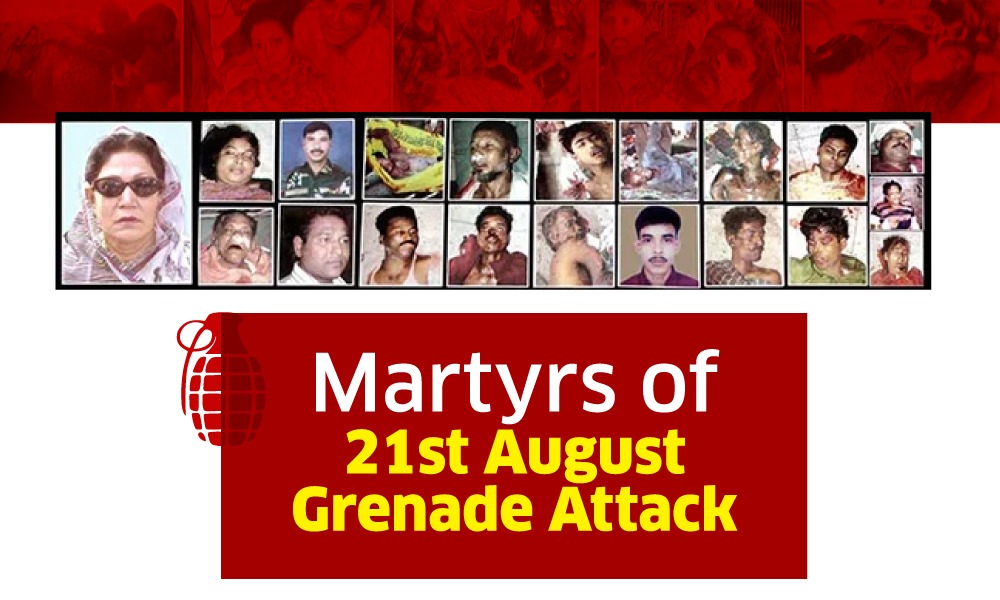

A consistent political pattern runs through the custodial death crisis: Awami League leaders and activists are disproportionately among the dead. This is not incidental. It follows a broader campaign marked by thousands of politically motivated cases, mass arrests, and prolonged detention that target one political camp with unusual intensity. Charges are often broad and weak, arrests frequent and sweeping, and release is rare, creating a detention pipeline that punishes affiliation rather than adjudicates guilt.

List of Awami League leaders and activists dead while in judicial custody

Within this framework, custody functions less as a tool of law enforcement and more as a mechanism of political punishment. Extended remand, repeated transfers, limited access to lawyers, and neglect of basic medical needs are not anomalies; they are features of a system designed to wear detainees down. The result is predictable: deaths that occur after arrest, during remand, and amid documented neglect.

Whether there’s a case or not, bring Awami League criminals under law.

Seen together, these outcomes form a visible pattern, not a coincidence. Arrest is followed by harsh custody; harsh custody is followed by injury, illness, or collapse; and death is followed by routine explanations and closed files. The repetition matters. It shows intent in practice, if not on paper. When one political group bears the brunt of lethal custody, the conclusion is unavoidable: under the Yunus government, detention has been repurposed into a political instrument, with fatal consequences.

When deaths occur in custody, the official response is often predictable. Authorities point to illness, suicide, or injuries sustained before arrest, framing each case as an unfortunate but unavoidable event. Yet these explanations rarely withstand closer examination. Families receive bodies with clear signs of abuse, while records show delayed or inadequate medical care. Promised investigations, when they happen at all, remain internal and opaque, offering little clarity and almost no accountability.

Unanswered Questions Surround the Surge in Custodial Deaths

Over time, this pattern has come to define the government’s approach. Instead of confronting the problem, the Yunus administration has relied on silence and procedural language. There have been no consistent demands for independent investigations, no visible effort to reform custodial practices, and no signal that deaths in custody will carry serious consequences. This absence of action has allowed harmful practices to continue while responsibility is quietly deflected.

Deaths Behind Bars: State Accountability and Required Action

As a result, these deaths can no longer be viewed as administrative lapses or isolated failures. They reflect political choices. By failing to intervene, investigate, or reform, the Yunus government has become complicit through inaction.

A state that takes people into custody assumes full responsibility for their safety; when it repeatedly fails to protect them, it undermines its own moral authority. In this context, custodial deaths stand as one of the clearest measures of the Yunus government’s failure to govern responsibly.